Fiona Tells

I would like to introduce you to the most unknown and mysterious region of Italy.

With small stories, I will tell you about my Calabria, its people, and its natural beauty.

There is also a written interview in german (soon to be translated) about me, Fiona, and our farm here.

S1. E1 — How did I get to Calabria?

When I met my husband Francesco, I knew he had grown up in Rome and worked in Milan, but soon discovered that his heart beat for Calabria, the home of his paternal ancestors.

Born and bred in Vienna, I did not know much more about Italy than the average Austrian tourist — the Adriatic Sea, Grado, Bibione, something about Florence, and a bit of Rome.

When Francesco talked about ‘his’ Calabria, which he knew mainly from holidays and his father’s stories, I asked him where it was located. He explained that it was situated even further south than Puglia, towards Sicily. I was terribly irritated, because I had visited the town of Santa Maria di Leuca in Puglia – at the very tip of Italy’s stiletto heel – and had been told that it was the southernmost point in Italy. Had I slept through my geography lessons at school? How was it possible there was something even further south? Shortly thereafter, I understood the relationship between Puglia (the heel), Calabria (the toe), and Sicily (the island).

S1. E1 — How did I get to Calabria?

S1. E2 — My first trip to Calabria

What an adventure! It was January 2001. There were no direct flights from Germany or Austria at that time, so I flew first to Rome and then to Lamezia Terme. Back then, you had to carry your suitcases between the airplane and the airport. When I arrived, it was evening and I couldn’t see much, but I remember the curves of the mountains one by one ….

The next morning, I had a big surprise: a breathtaking view, beyond my wildest dreams. The Savuto River Valley was surrounded by a sea of green mountains and picturesque villages. That was the moment when I thought …YES! I could live in this part of the world! Surrounded on either side by the glittering sea are the majestic mountains – a very important landscape element for an Austrian! – like the cherry on top of a cake.

S1. E2 — My first trip to Calabria

S1. E3 — The contrasts in Calabria

In winter, you can ski in Sila and on the Aspromonte. In summer, you can dive into the deep blue Tyrrhenian Sea or into the turquoise waters of the Ionian.

You can also go for a walk/trek in the largest natural park in Italy, and those who are not bitten by wolves or bears can also swim in the fresh lakes of the Pollino or Sila. Just kidding!

There are also attractions for the culture enthusiast. One of my first trips took me to the castle of Vibo Valentia, which is now a state museum. There I found descriptions of explorer Friedrich Leopold Graf Stolberg’s 18th century journey to Calabria, which was commissioned by the Emperor of Austria.

S1. E3 — The contrasts in Calabria

S1. E4 — The Tyrrhenian side

I want to tell you some things about the Calabrian sea on the Tyrrhenian side, which is the closest sea to our home. From the beach, the sea is immediately very deep, which is why the color of the water is so dark. This stretch of coast is characterized by strong, reliable winds that make it ideal for kitesurfing.

My favorite beach, located in Gizzeria, is called Hangloosebeach and is very popular with kitesurfers. It is not only a meeting place for sport, but also has a stylish bar and a trendy restaurant.

Relaxation and ‘coolness’ pervade the place, with sport offerings and entertainment for both young and experienced surfers as well as regular beachgoers. In May and June, before the summer season begins, the beach draws kitesurfers from all over Europe. The Aeolian Islands are not far away and on clear days you can see them perfectly.

S1. E4 — The Tyrrhenian side

S1. E5 — The classic Calabrian

Yes it’s true, the classic Calabrian man is “scuro ed oscuro,” but for me as a real typical Austrian, the true Tyrolean man is also mysterious. I am convinced this particular temperament is due to living in the mountains.

Mountain people are often suspicious of foreigners as potential enemies. But unlike the Tyrolean, who smiles as soon as he identifies the foreigner as a tourist carrying money, the Calabrian smiles upon recognition that there is no real danger. In all the world, I have found nothing more hospitable than a Calabrian family who opens its heart.

S1. E5 — The classic Calabrian

S1. E6 — Men on the street

— Then —

In the villages of Calabria, it is primarily men (of all ages) who can be found in the streets: standing, sitting or playing cards and passing the time with a beer, a glass of wine or a coffee in hand. The women are at home, chaste and mainly occupied with cooking — there is always an abundance of food, perhaps too much – or tending the vegetable garden and pickling their produce for the winter.

— Now —

Between the hours of 1:00 and 5:00 PM, the villages seem empty, as each person spends the siesta in his or her own way. In the cities of Southern Italy, gender equality has been accepted in a special way: women frequent bars or clubs in groups of at least two and are happy to be among friends.

S1. E6 — Men on the street

S1. E7 — A small anecdote

In the early years of our marriage, we traveled to the Calabrian town of Martirano Lombardo primarily in the summers to visit my in-laws’ house. One day, my father-in-law asked if I wanted to accompany him to Santa Croce. Being very curious and eager to absorb everything, of course I agreed.

We drove along some dirt roads and soon arrived at a farmer’s house. My father-in-law spoke to the couple who lived in the house and, before I knew it, tomatoes and other produce were being loaded into our car and we were on our way back home. What a great disappointment! Because of my limited Italian, I thought we would be making a trip to a famous church and not a house in the middle of nowhere, or … stay tuned for my next posting to find out!

S1. E7 — A small anecdote

S1. E8 — The real first time in Santa Croce

The next day, I put my daughter in the stroller and thought: If I bring up my child in a place that loves children, I will be protected from a bunch of angry looking people. I was curious to get to know the villagers a little better.

She in the stroller and I on foot, we walked uphill and downhill, finally arriving in Santa Croce where we met the farming couple whom my father-in-law and I had visited the day before. They greeted me with “le facce scure,” the inscrutable expressions that are often typical of Calabrians. I immediately pulled my baby out of the stroller and positioned her between me and the man.

He spoke to me in Calabrese, a dialect derived mainly from ancient Greek, and I tried my best to answer in a mixture of Spanish and a little Italian. In practice, neither one of us understood the other, but thanks to the little girl’s wide smiles, the man’s demeanor softened. His name is Ricciotti, and he and his wife became my first teachers in Calabria.

S1. E8 — The real first time in Santa Croce

S1. E9 — Una terrona

So, I learned a lot from Ricciotti and Giovanna: I got involved in all of their activities and my daughter grew up healthy and happy playing among goats, sheep and dogs and eating good food created with fresh ingredients.

After some time, they offered what was for me the highest compliment possible:

“You are not really from the North. In your heart, you are a terrona like us.”

The word “terrona” is an offensive term for a person from Southern Italy that expresses all of the superiority of the North. However, when used by a Calabrian, proud and indomitable, it is a great honor.At this moment, I knew I had found a new home.

S1. E9 — Una terrona

S1. E10 — Wash your hands in the mountains

I had another teacher who lived in the mountain above Martirano, in a place called Molinara. He taught me many things about the South: Which plants you can use to make particular grappas, how to wash your hands by rubbing certain flowers that grow near the springs, and so on.

Sometimes we would walk together. He would bring his cows to graze, and we would sit under a large cherry tree while he shared stories of his difficult and full life. He would cut two branches from the tree and we would enjoy the succulent black cherries directly from those branches, savoring the view of the Savuto Valley in front of us.

S1. E10 — Wash your hands in the mountains

S2. E1 — Mourning

Here in Calabria, death remains an important part of life. The rituals surrounding death and mourning (Lutto) are respected and observed, in particular the moving tradition of the open coffin.

It is customary for the widow (usually the wife is the one left behind) to receive guests at her home.

As the mourners arrive to pay their respects, she “reintroduces” them to the deceased, explaining who they are and telling stories of their shared life experiences. The circumstance is very deep and emotional for everyone. Another common practice is for guests to leave food near the coffin for the ancestors who will attend the dead.

S2. E1 — Mourning

S2. E2 — Reggio Calabria

Let’s get back to enjoying life, so let’s go to Reggio Calabria.

The largest and most populated municipality of Calabria! Since the Salerno-Reggio Calabria highway was completed in 2016 (55 years after work began!), it is very easy to reach the city by driving just an hour and a half.

After parking, it is mandatory to stroll along “the most beautiful kilometer in Italy,” as writer and poet Gabriele d’Annunzio defined the Lungomare Falcomatà, Reggio’s seaside promenade.

Along the way you will encounter some very nice bars and ice cream shops where you can also find delicious aperitifs.

Surely you will hear German and English spoken. And often you will meet Calabrians who lived their young lives abroad and welcome the opportunity to use the languages of their youth.

S2. E2 — Reggio Calabria

S2. E3 — Riace Bronzes

After the promenade, it is always interesting to visit the National Museum of Reggio Calabria. Exhibitions vary, highlighting items from the Stone Age until the late Roman times, and the museum is the only one of its kind to be built around a necropolis.

However, the main attraction is surely the Bronzi from Riace, two life-size Greek statues of naked bearded warriors from approximately 460–450 BC that were discovered in the sea near the town of Riace in 1972.

The Calabrian government endured a long battle to have the bronzes returned to the National Museum following their renovation and initial discovery. Although there were concerns about the security of the artwork, everyone can now rest assured that they are safe, sound … and magnificent!

After a few hours of art and culture, why not stop across the street to the renowned Gelateria Cesare for a delectable ice cream? Take it to go, and admire the charming houses and shops while enjoying a leisurely walk along the main road.

S2. E3 — Riace Bronzes

S2. E4 — Red Onions from Tropea

A great excursion is to visit the towns of Tropea and Pizzo! When the day arrives, one should leave early and drive directly to Tropea. It is surely the most well-known town in Calabria.

The water is a turquoise color that most people associate with the Caribbean Sea, and the city is built on a rock overlooking these blue waters, surrounded by fine sand. The combination provides an irresistible invitation to enjoy the sun and take a long dive.

In the city of Tropea, one can find beautiful small shops and very inviting trattorias and gelaterias. Wandering around quickly becomes an occasion to notice nice mansions and reach the Duomo, otherwise known as the dome of the Norman Cathedral. But above all, the most famous product of Tropea is the humble onion — red and sweet and valued by the whole culinary world.

S2. E4 — Red Onions from Tropea

S2. E5 — Children’s Beach in Pizzo

One day we went to the town of Pizzo in search of the perfect beach for our little one. We considered our spot quite carefully, as the Tyrrhenian Sea becomes very deep very quickly, and for that reason can be dangerous for small children.

After our swim, I realized I had forgotten to bring a spare diaper. As there were no open shops (it being riposo, or Italy’s midday siesta), I went looking for an Italian mama in possession of spare diapers.

After initial failures, I finally got lucky when I found the family of a fisherman with innumerable children, one of whom was the age of our daughter. In addition to finding the diaper, we found the perfect swimming spot. The fisherman had created a pseudo swimming pool in the shallow waters of the sea; we liked it so much, we returned there many times over the years.

S2. E5 — Children’s Beach in Pizzo

S2. E6 — Giada the dolphin

The daughter of the fisherman, whose name is Giada, became the best beach-friend of our daughter Clarice. Petite, tanned, with green eyes, Giada was the opposite of Clarice, who was tall and fair and with grey-green eyes. The two girls liked each other from the moment they met.

We wondered how Giada was already jumping and diving in the water like a dolphin, while Clarice still used arm floaties. I asked Giada’s mother how her daughter learned to swim so well at so young an age. Her method was simple: When Giada was a baby, her brothers threw her into the water to see what would happen.

The experiment worked well and, by age three, she was absolutely comfortable in the sea. Once Clarice learned to swim, the girls spent whole days together at the seaside collecting “golden sand” in bottles, eating fresh fish and french fries, and playing in the water. The other beachgoers called them “the light one” and “the dark one,” but no one could tell them apart until they emerged from the sea.

S2. E6 — Giada the dolphin

S2. E7 — Tartufo di Pizzo

And now Pizzo! The city has witnessed tragic historic events. General Joachim Murat, King of Naples and brother-in-law of Napoleon, fled Naples in 1815 and took refuge in Pizzo, where ultimately he was betrayed, tried for treason, imprisoned in Castello di Pizzo, and sentenced to death by firing squad.

Thankfully, Pizzo is also blessed with good fortune. Due to an astonishing location and a romantic terrace overlooking the sea, the view from Pizzo yields breathtaking sunsets. It remains a magnet for couples in love and has been the location of more than a few engagements.

However, Pizzo’s greatest claim to fame is its Tartufo. Almost as famous as the venerable Austrian Sachertorte, but in fact much more delicious, Tartufo, which originated in Pizzo, is arguably the best ice cream in the world. There are many purveyors of Tartufo in the town, but the place I prefer is Gelateria Chez Toi. The owner prepares the tartufi in a very small kitchen and if one is extremely lucky, it is possible to watch the master at work.

S2. E7 — Tartufo di Pizzo

S2. E8 — The Cave-Church of Piedigrotta

Situated just outside Pizzo, you can find and visit a church built into a cave. The church is called Piedigrotta, and I would like to tell you its legend.

During the 17th century, after a violent storm, a ship sank in the surrounding waters, but before the vessel went down, the captain and crew gathered below deck to pray for their lives before a painting of the Madonna. (At that time, every ship had an image of the Madonna on board.) The sailors promised that if she saved their lives, they would build a church in her honor and, in fact, the crew made it safely to shore.

The following day, as they were searching for remnants of their ship, they found the painting, which they brought directly to a nearby church where they celebrated a thanksgiving mass. The next day, however, the image was gone, only to reappear again on the shores. This scenario repeated itself many times. Eventually, the residents of Pizzo decided to place the painting in a small cave dug into the tufa (a variety of limestone), close to the sea. This cave became the present-day Chiesetta di Piedigrotta.

In the 19th century, local sculptors began to add artwork to the cave by carving stone figures representing Christ and the saints. Today, one can view not only many religious carvings, but also politically inspired scenes, such as the Kennedy-Brezhnev meeting! The cave-church continues to change and grow as more sculptures are added. People can visit from spring to autumn; in wintertime, the attraction is often flooded with seawater.

S2. E8 — The Cave-Church of Piedigrotta

S2. E9 — The Calabrian Diaspora

People from Calabria emigrated in different waves over the last hundred years. The first exodus, which occurred at the end of the 19th century, was characterized by young men leaving their homeland in search of riches associated with the great American dream, but always with the intention of returning. Those who made it back bought land, often from their former landlords.

The second wave took place in the 1930s. There were so many departures that Mussolini issued a ban on emigration in order to stop the tide! In the 1960s, most male emigrants left Calabria with their wives to settle in popular destinations such as Switzerland, Germany and the North of Italy. However, many mothers returned home to Calabria when it was time for their children to begin school. The fathers remained elsewhere to continue working and sending money home.

Many families built houses for themselves and future generations, which demonstrated their strong desire to remain connected to their ancestral homeland. Today, things are different: whoever decides to emigrate packs the luggage, chooses the destination, and typically stays forever.

S2. E9 — The Calabrian Diaspora

S2. E10 — The Hard Heads

My husband advises me to avoid making generalizations and judgments, but …. people from Calabria are hard-headed and stubborn, just like the Viennese. However, there is an important distinction between them: The Viennese do not have similar strong feelings about honor and family.

For example, if I have a problem with a Calabrese, I can be certain that nobody – really, not one relative — from that person’s family will ever have contact with me or my family again. And by “family” I mean extended family, including aunts, uncles, cousins, etc.

These circumstances mark the end of friendships, even for family members who had no part of the issue that created the tension. In this regard, Calabrese society is more similar to Arab culture than to European culture!

S2. E10 — The Hard Heads

S3. E1 — Catanzaro

We live exactly between the modern capital of Catanzaro and the ancient capital of Cosenza, and in the following episodes I will tell you about both.

Catanzaro rose to power during the Byzantine period and was a major stronghold against the Saracen attacks from 906 A.D. onward, reaching its peak during the Kingdom of Aragon. Beginning in the Middle Ages, the city was the European center of production for silk and damask fabrics, but the thriving textile industry was struck by silkworm disease in the early part of the 19th century, causing its decline and eventual demise. Weavers fled the city or dedicated themselves to other pursuits, and Catanzaro’s economy never regained its ancient splendor.

The city, built on three hills that dominate the surrounding area, is accessible by high bridges. The most imposing of these, called Fausto Bisantis Bridge, is built on a single arch, the widest in Italy. When you arrive in Catanzaro at night, it appears like Utopia. From the darkness emerges a fantastic and illuminated aerial city.

S3. E1 — Catanzaro

S3. E2 — Cosenza

Cosenza is a city famous for its history and its characters. Germans know it from the poem Das Grab im Busento, written by August von Platen-Hallermünde (1796-1835), which speaks of the city, its river Busento and Alarich I, King of the Visigoths.

The first barbarian to conquer Rome, Alarich died in Cosenza and was buried under the river along with his horse, his armor and an immense treasure. The digging of the grave and restoration of the riverbed after the funeral were performed by Roman slaves, who were subsequently killed by Alaric’s soldiers in order to keep secret the exact location of the burial site. The king’s tomb and treasure remain a mystery for archeologists!

Cosenza impresses also for its Norman Castle (likewise called Hohenstaufen Castle or Swabian Castle).

In the old town, I suggest a visit to the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi, the Church of the Dominicans and, naturally, to the Duomo. Next to the Duomo, there is a cozy restaurant featuring excellent Calabrian cuisine and wine.

In the newer part of the city, along the street called Corso G. Mancini, you will find an open-air museum displaying sculptures by famous artists – such as Salvador Dalí, Giorgio De Chirico, and Giacomo Manzù — donated to the city by the art collector Carlo Bilotti.

S3. E2 — Cosenza

S3. E3 — Travelling in the South

I will now touch on a difficult issue about which I often get questions: the mafia in Calabria, known here as ‘Ndrangheta. First, I would like to state clearly that travelers to the South are not affected by the ‘Ndrangheta and, indeed, they will not even perceive its existence.

Much has been written about the origin of this criminal phenomenon, in particular why it developed in Southern Italy. There are surely direct connections between the presence of ‘Ndrangheta and the region’s former severe poverty and widespread social injustice. However, organized crime is not unique to this part of the world; it has also developed in northern Italy, Germany, and in fact all over Europe.

Those of us without familial connection to the mafia prefer to stay far away from it, as no good can result. The exceptions are the heroic people and extraordinary organizations that fight for justice by overtly opposing this criminal system.

S3. E3 — Travelling in the South

S3. E4 — San Giovanni in Fiore

A hot summer day is the perfect time to travel to San Giovanni in Fiore because the village is located is the Sila Mountains, where the weather is much cooler than along the seaside. The most famous son of this city is Gioacchino da Fiore (1135-1202), abbott of the Cistercian Abbey of Corazzo and founder of the Order of Florense. Da Fiore studied the Revelations of the Holy Scriptures with permission from Pope Lucius III. A theologian and an accomplished intellectual who contemplated humanity, da Fiore influenced Dante Alighieri, who placed him in the paradise of the Divine Comedy among the blessed wise men. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI stands out among the many scholars of da Fiore’s theology.

The art of goldsmithing has developed over time in the town of San Giovanni in Fiore. A few times each year, traders riding donkeys would bring gold into the city with which artisans produced jewelry and ornaments that became famous all over Calabria. Today, the local museum displays historical objects of the highest workmanship.

S3. E4 — San Giovanni in Fiore

S3. E5 — Hospitality in Calabria

Anyone who has ever been a guest in a Calabrian home knows how necessary it is to have an expandable stomach and a well-padded bottom. After a heartfelt greeting, you will be seated almost immediately at the table and, before you know it, the hostess will begin shuttling between the kitchen and the dining table. Just when you (mistakenly) think you have control over the amount and array of foods on your plate, the most scrumptious delicacies will arrive!

After the appetizers and the first course, the meat will be served, accompanied by various potato dishes – and then the road of suffering really begins. If you are able to think straight during this period of consumption, you will observe that the hosts eat comparatively little while urging their guests to consume more and more. Vegetables and salad will follow along the same pattern, and if you are lucky, you may be able to avoid a second piece of cake.

By the end of the meal, you are happily indulging in coffee and grappa, without which it seems the world will collapse. When you feel the only way home is to crawl (or roll), you can imagine a grin on the hostess’s face that means “we won once again!”

S3. E5 — Hospitality in Calabria

S3. E6 — Maddy

Today, I will tell you a story about when our daughter was mistaken for a young girl named Maddy, who, at the time, had recently disappeared.

One day, Clarice and I went with some Austrian friends to visit Nicastro, a medieval city near our home. We had just finished touring the ruins of the Norman Castle and were walking along the old road when a woman came out of nowhere, shouting (in Italian, of course): “I found Maddy!” She grabbed Clarice’s free hand and proceeded to pull her. Our tall, muscular companion, whom Clarice calls ‘Beutelratte’ (Opossum), jumped immediately to our daughter’s defense. Likely frightened by the sheer size of our Austrian protector, the woman withdrew from the scene and the crowd slowly dissipated. What a spectacle! In reality, the only similarities the girls shared were their age and their hair — blonde in color and parted down the middle, which is common for “Nordic” children — but here in the South, there are very few fitting that description.

S3. E6 — Maddy

S3. E7 — Tiriolo

Called “The Land of Two Seas,” Tiriolo towers over the narrowest isthmus in Italy, a point from which you can see both the Tyrrhenian and Ionian Seas. During the 4th century B.C., Tiriolo was inhabited by the Bruttians, its indigenous people, and was known as an important center.

Today, the residents of the city claim it is possible to find many artifacts, such as old coins, shards and other ancient objects, simply by digging in the earth. Recently, during an excavation for the foundation of a new house, workers discovered a tomb; unfortunately, the construction machinery left “teeth marks” on the ancient grave.

The area’s artifacts and relics, recovered over time, are now housed in a small architectural museum, Antiquarium Civico. One of the most interesting of these is a plaque from the Roman period on which is engraved the rules concerning how to organize a party or festival. The original is displayed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

S3. E7 — Tiriolo

S3. E8 — The Pacchiana

Tiriolo is home to the Regional Costume Museum, which is dedicated to the culture and history of traditional Calabrian clothing. The main attraction is the “pacchiana,” a traditional style of dress worn by women beginning in adolescence and passed down from mother to daughter.

Created and enriched with quality embroidery, the pacchiana was frequently part of the marriage dowry and often demonstrated a woman’s social status. The dress’s details, such as colors and embellishments, corresponded to a woman’s daily routine, her milestones (such as festivals or mourning periods), and her stage of life (for example, childhood, adolescence, or adulthood).

The pacchiana consists of a wide skirt that is decorated at the bottom and artfully rolled up and knotted over the rear end. The first layer is a long white shirt followed by a dark brown shirt for unmarried females, a red shirt for married women, or a large black cloth wrapped around the body for widows. On top of these layers is a skirt of at least 7 meters’ length, which combines with a tightly laced corset to highlight the female form. Some people say that once upon a time, women kept food in the neckline of their pacchiana and, in wintertime, stored small wooden boxes of silkworms in their dresses to keep themselves warm and the silkworms protected through the colder months.

As no modern woman wants to be considered “backward,” the pacchiana has almost completely disappeared from contemporary life. However, many Calabrian women save money to purchase one for their burial. I had my own pacchiana custom made, especially for me. It is so extravagant and colorful that people think it is one of Vivienne Westwood’s haute couture creations!

S3. E8 — The Pacchiana

S3. E9 — The Vancale

The “vancale” is an important component of the “pacchiana” (the traditional popular Calabrese female dress) and the “corredo,” or wedding trousseau. It is a shawl at least two meters long, made from silk or wool, with horizontal stripes that were traditionally woven in shades of black or red.

The items comprising a wedding trousseau were traditionally kept in a wooden chest (or “banca” in Italian) until the wedding, for which the precious shawl served as a decorative cover.

The word vancale is derived from the word “vanca,” which is a modification of the word “banca.” The vancale was often the only possession a female would bring to her new life as a married woman.

S3. E9 — The Vancale

S3. E10 — Amantea

Amantea is a very fascinating small city and seaside resort, located between the shore and the mountains and not too far from our home. People say it is an ideal spot for body-surfing!

In ancient times, the city was a Greek colony, and the name Amantea first appeared in the 7th century after Christ. In 839 A.D., Amantea was conquered by the Arabs, who established an emirate there, but by 885 A.D. the Byzantines, with the help of the local population, won it back.

In 1630, the Prince of Belmonte bought the city, but the citizens organized a revolt, freed the city, and ultimately repurchased it. From that time on, the citizens of Amantea reported directly and only to the King of Naples.

During a visit to this area, one should not miss a visit to the Duomo and the Church of San Bernardino da Siena, formerly part of the Franciscan monastery. For those with a sweet tooth, I advise Gelateria Sicoli, which sells the best pistachio ice cream in the region, and also offers a pistachio pesto to take home.

S3. E10 — Amantea

S4. E1 — Squillace

Today we will move to the other side of Calabria, on the Ionian Sea, to visit “The Coast of the Oranges.”

After a relaxing day at the beach, when it starts to cool down during the afternoon, one can go and visit Squillace, a charming medieval mountain village that is also an interesting archeological site. The city was already important during the Magna Graecia times, when it was called Skylletium, and a well-known legend attributes its founding to Ulysses, the hero of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey.

In ancient Roman times, the city had yet another name, Minerva Augusta Scolacium, and was home to Aurelius Cassiodorus, who was known as “the last Roman and the first Italian.” Another worthwhile stop near Squillace is the Church of Santa Maria in Roccella, built by the Normans at the end of the 11th century. Its extensive Byzantine ruins include an amphitheater, thermal baths and an aqueduct.

S4. E1 — Squillace

S4. E2 — Cassiodorus’ Basins

Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus, came from an important aristocratic family of senators of the Roman Empire.

After a brilliant political career as a statesman and a scholar, he retired in old age to his family estates in Squillace. There he founded the monastery of Vivarium, which included a library and a biblical studies center and became a place of preservation for classical Greek and Latin literature.

The name Vivarium (akin to aquarium) is derived from the many natural basins, or tanks, that are carved into the rocks at sea level. In Cassiodorus’ time, these tanks were used for fish farming, but the area still impresses today for its crystal clear seawaters and white sands.

The basins can be accessed via Copanello Beach — either by swimming along the rocks or, with more effort, by climbing among the rocks and shrubs. In either case, they are well worth a visit.

S4. E2 — Cassiodorus’ Basins

S4. E3 — Paola

Another very interesting excursion brings us to the city of Paola, the most important pilgrimage destination in all of Calabria.

Paola is the birthplace of Saint Francis of Paola, who was named after Saint Francis of Assisi and is perhaps the best known saint of the South. Primarily an ascetic, Francis was known for his humility and open and friendly nature to all people, regardless of wealth or social standing. He established the Roman Catholic Order of the Minims (in German, Paulaner) in the 15th century; the word “Minim” refers to living as the smallest or the least by embracing humility, simplicity and plainness.

Francis was considered to be a great thaumaturge, or “worker of miracles.” Of the many miracles attributed to him, one of the most astonishing occurred in 1464 when he reportedly crossed the Strait of Messina to Sicily by laying his cloak on the water, tying one end to his staff as a sail, and crossing with one of his brethren to the other side. In advanced age, Francis was sent by the pope against his will to the French court of King Louis XI, where he died after almost 20 years.

Today, people invoke his name for help with infertility and some say the fountain in the Sanctuary of St. Francis in Paola produces water that brings miracles to those who drink it. In my hometown of Vienna, one can still feel Francis’ presence keenly at Paulanerkirche (the Paulaner Church) and along Paulanergasse (Paulaner Street).

S4. E3 — Paola

S4. E4 — Fiumefreddo Bruzio

Francesco da Paola’s mother’s name was, coincidentally, Vienna (my hometown)! She was born in Fiumefreddo Bruzio, a marvelous hamlet built on a rocky promontory 200 meters above the Tyrrhenian Sea near the town of Paola.

It is worth passing through Fiumefreddo (meaning cold river), which in 2005 was named one of the borghi più belli in Italia, or most beautiful villages in all of Italy. Fiumefreddo is home to the ruins of an ancient castle (called Castello della Valle or Castello Freddo) that conjures up fantasies of medieval times. Its large 16th century entrance portal, which was created in the style of Michelangelo, was very fashionable then and is worth a visit today.

In 1531, the fiefdom was entrusted by the Emperor Charles V Habsburg to the Marquis Ferdinando de Alarcon-Mendoza, the Viceroy of Calabria and Marquis of the Valley. Between 1806 and 1807, the area was heavily damaged by Napoleonic troops, which is why, apart from the earthquakes, little of the medieval fortress remains.

S4. E4 — Fiumefreddo Bruzio

S4. E5 — Scilla e Cariddi

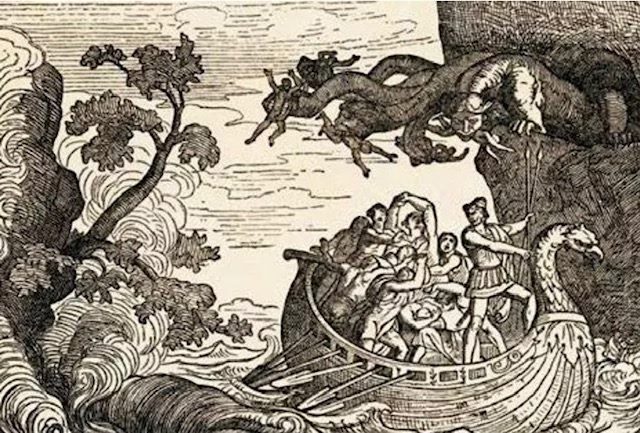

Scylla and Charybdis were terrible monsters of ancient Greek mythology that guarded and controlled opposite sides of the Strait of Messina, located between Sicily and Calabria.

Scylla was the smaller of the two (although quite imposing, with six heads!) and inhabited the Calabrian side of the Strait, while Charybdis was a terrible nymph, daughter of Poseidon, god of the sea, and Gaea, goddess of the earth, who lived on the Sicilian side.

First described by Homer in The Odyssey, the monsters were regarded as maritime hazards located in close enough proximity that each posed an inescapable threat to passing sailors. At its narrowest point, the Strait of Messina is only 3.1 kilometers wide; avoiding Charybdis meant passing too close to Scylla and vice versa. Some attribute to this story the expression “lesser of two evils” and the idiom “between a rock and hard place,” both of which signify a dilemma of two poor choices, or, in the case of ancient mariners, two perilous obstacles. In fact, Scylla has been rationalized as a sandbar or a shoal and Charybdis as a natural whirlpool.

The Messina Strait today has a very dark color with currents reaching 200cm per second — strong enough to rip seaweed from the ocean floor. Due to wave patterns, the Strait frequently produces eddies, which are called the mouths of Charybdis. The sea is so tormented and iridescent that one can truly imagine how this incredible place has inspired and influenced mythology.

Today the town of Scilla is a fishing village that invites you to take a quiet walk. In particular, it is worth going to Chianalea, where there are many small restaurants offering fresh fish. In October, the swordfish festival is celebrated in honor of traditional fishing practices: all in all, a unique experience.

S4. E5 — Scilla e Cariddi

S4. E6 — Black garbage bags

Today I would like to share with you a little adventure I experienced with an acquaintance of mine.

I had only recently settled in Calabria when this Austrian friend came to visit. Like almost every visitor I have hosted over the years, she brought with her two suitcases: one physical bag full of clothing and items for her trip, and another metaphorical bag full of prejudices. As is always the case, the latter suitcase is much heavier and can be emptied only slowly and with a lot of effort.

To show her the beauty of Calabria’s capital, I brought her to see Catanzaro. At that time, I was still unfamiliar with the traffic patterns. For cars, the entrance to the city is on one side of the hill and the exit is on the other, but unfortunately, I found myself at the exit before even entering!

Consequently, we were situated right under the Catanzaro Bridge, built by Riccardo Morandi in 1962 and renamed Il Ponte Bisantis in 2001 in memory of city native and senator Fausto Bisantis. Although the bridge is famous for its one-arch concrete structure, the area beneath it was (and still remains) a landfill, filled with many black garbage bags that, on that day, had swelled due to the heat.

My friend became very nervous and frightened, convinced that the bags were full of body parts severed from corpses. She was so hysterical that she prohibited me from stopping the car and opening the window to ask for directions. It took us hours to find our way back to the highway. Clearly, she had a strong prejudice; nevertheless, deep down I was happy she didn’t have a heart attack!

S4. E6 — Black garbage bags

S4. E7 — Rossano

Let’s take a tour of Rossano! The city is chock full of attractions, but the main highlight is surely the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis, a 6th century illuminated manuscript also known as the Rossano Gospels.

The Latin word “purpureus” refers to the reddish-purple hue of its vellum pages, which are richly decorated with scenes from the New Testament. The Codex includes the complete Gospel of Matthew and parts of the Gospel of Mark as well as a letter from Eusebius of Caesarea, believed to have been written in Syria in the 6th century and ultimately saved from the Arabs by monks who brought it to Calabria a century later.

Another very interesting attraction is the Cathedral of Saint Mary of Acheropita (also called the Rossano Cathedral), inside of which is preserved a Byzantine acheropita icon of the Virgin Mary from approximately the 7th century. Acheropitas (or acheiropoieta in medieval Greek) refer to Christian icons (invariably images of Jesus or the Virgin Mary) that are believed to have come into existence miraculously, without the use of human hands.

Also noteworthy is another church, dedicated to San Nilo, rebuilt during the Baroque period. In addition, Rossano is the Italian center of licorice production. In the 16th century, the Amarelli family became interested in the roots of a particular plant that grew wild on their Calabrian estates; today, Amarelli is one of the oldest family companies in Italy and known throughout the world for its licorice products. Visitors can tour the Giorgio Amarelli Museum of Licorice (awarded the Guggenheim Culture and Business Prize in 2001) to learn about the history of the family business through engravings, documents, books and photographs.

S4. E7 — Rossano

S4. E8 — Sibari

Approximately 100 kilometers north of us, close to the Gulf of Taranto on a fertile plain, lies the village of Sibari, which was founded in the 1960s.

Just a few kilometers southeast of the town, however, is the archaeological site of Sybaris, which was founded quite a bit earlier – in 720 BC! During the Magna Graecia, when coastal areas of Southern Italy were colonized by various ancient Greek city-states, Sybaris was the seat of a very important, wealthy and powerful city. Its inhabitants became famous among the Greeks for their hedonism, feasts, and excesses, to the extent that today we use the word “sybarite” to refer to a person who has a decadent or luxurious lifestyle.

In 510 BC, there was a rebellion in Sybaris, after which the wealthiest citizens fled south to the city of Crotone (also: Kroton, Cotrone), and Sybaris was completely destroyed. It was not until 1932 that the ancient location of the city was rediscovered. Archaeological excavations unveiled the ruins in 1969 and can be visited today.

As well, the National Archaeological Museum of Sibaritide, a small, fascinating collection where you can learn more about the objects unearthed during the excavations, is located in Laghi di Sibari. Kroton has a history similar to its neighbor Sybaris. It was founded by the Greeks in 710 BC and subsequently conquered in 277 BC by the Romans during their southern expansion. Nearby Sibari is the marine-protected area of Capo Rizzuto, the largest marine park in Italy, where the sea shines from blue to emerald green. Dedicated to environmental and archaeological preservation, Capo Rizzuto offers numerous activities, such as guided tours, scuba diving visits to the seabed, sailing excursions, and boat trips.

S4. E8 — Sibari

S4. E9 — Not all that glitters is gold

In Calabria, municipal politics work in their own special way. By this, I mean to offer a thinly veiled euphemism for frequent cronyism and nepotism. Given this situation, one can easily imagine that many intertwining favors and debts remain long after the votes are cast. As a result, inefficiency and incompetence become the norm and productivity suffers.

The local post office is a prime example. Workers are often overloaded, and it can happen that you spend half a day waiting there for a routine errand.

Allow me to share a small example to illustrate the point: A middle-aged daughter goes to pick up her mother’s pension at the post office. Since the illiterate mother is bedridden and unable to go in person, the daughter shows the postal worker all of her mother’s personal documentation, including the identity card that is signed with three crosses in place of her signature. The postal official is intent on following the procedures to the letter, however. She refuses to accept the papers from the daughter and demands to see the elderly lady in person before releasing the pension — even though she personally knows the family and the mother’s health situation. The daughter is left with no choice but to take her mother to the post office by ambulance.

I relay this story to demonstrate that “not all that glitters is gold.” In other words, I hope to present a faithful – albeit not always bright and shiny – account of my beautiful yet imperfect corner of the world.

S4. E9 — Not all that glitters is gold

S4. E10 — Hannibal's Bridge

In the Savuto valley, near Scigliano, there is a Roman bridge called Ponte di Sant’Angelo or Ponte di Annibale (Hannibal’s Bridge).

According to legend, the Cathaginian leader Hannibal crossed it with his elephants and armies at the end of the Second Punic War — although historians have never been able to confirm the event since, of course, there is no documentation.

Hannibal’s Bridge is actually one of the oldest bridges in Italy, from the second century after Christ, and remains under the protection of UNESCO. It was built with red tufa-limestone from a nearby quarry; has a single vault with two concentric arches; and measures a width of 3.45 meters, a height of 11 meters and a length of approximately 25 meters.

The bridge is part of the ancient Via Annia Popilia, the Roman road that conects Capua with Reggio Calabria, and is located near the commerical crossroads and military garrison of Ad Sabatum Flumen.

S4. E10 — Hannibal's Bridge